If You Want To Time The Market, Ignore Moving Averages

Submitted by Silverlight Asset Management, LLC on June 10th, 2019

Scary stock charts make for reliable clickbait, but not reliable profits.

The indicators vary. A common feature, though, is provocative terminology. For instance, headlines about a 'Death Cross' in the market will tend to stir more interest among casual market watchers compared to stories about Fed policy.

A conventional indicator that traders and the media often highlight includes moving averages. They commonly cite the 50-day, 100-day, and 200-day. The general belief is that moving averages provide important clues about market trends.

Consider the relationship between moving averages themselves. The dreaded 'Death Cross' happens when a 50-day moving average pierces a 200-day—signifying momentum is waning.

If a market or security is above key moving averages, it's perceived to indicate a healthy bullish trend. Conversely, when key moving averages are violated, it's interpreted as a sign the trend is likely turning bearish.

The S&P 500 index has been flirting with its 200-day moving average, setting the stage for columns like one MarketWatch recently ran titled: "U.S. stocks are dangerously close to a class 'sell' signal".

The article asserts that using the 200-day "would have gotten you out of stocks in October 2000 and in November 2007, before the brutal bear markets arrived."

The author adds this important caveat: "Sure, there are false positives too: Occasions when the market fell below its 200-day moving average, and then quickly rebounded. That occurred briefly in November 2014 and in August 2016."

The degree of false positives is where the rubber meets the road with technical indicators. And this is where many conventional signals that extrapolate current trends into the future, like moving averages, prove ineffective.

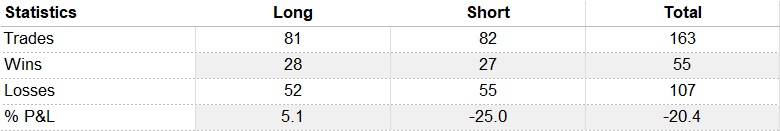

I ran a 5-year backtest. The strategy I tested had just two triggers: (i) go long the S&P 500 SPDR ETF (SPY) whenever the index closes above the 200-day moving average and (ii) go short whenever the index closes beneath the 200-day.

If a hedge fund were running this strategy, the manager would have been in and out of the market 163 times over the last five years, going long on 81 separate occasions and short on 82 occasions.

And the reward for all that activity? A cumulative loss of -20.4%.

Period of study: June 2014 - current. Source: Bloomberg.

Moving averages probably had predictive value in the past. According to the MarketWatch piece, a 2014 study by Meb Faber indicates that from 1901 to 2012, "getting out of stocks when the S&P 500 fell through its 200-day moving average would have more than doubled your ultimate returns—and cut your risks by at least a third."

Studying the past helps form a smart strategy. Yet shrewd investors also remember to play the game in front of them. Market dynamics change over time, which means strategies must also adapt.

Many conventional technical indicators extrapolate current trends forward. That's what moving average theories are based on, for example.

But the 200-day moving average may have been a much better indicator in the 1960s, when turnover was less rapid. Back then, the average holding period when someone bought a stock was eight years. Today, it's under a year.

Compressed holding periods might make the present trading environment choppier and more mean reverting, which would render moving averages a less effective forecasting tool.

Another factor that's changed is the degree to which companies buyback shares. The biggest pool of equity buyers since 2009 isn't retail or institutional investors, but rather the companies themselves. Firms buying their own shares have provided a steady bid during market selloffs, helping to curtail declines and extend the bull market.

A lot of trading in the modern landscape is executed by computer algorithms. To front run the robots, one must understand how they think. Folks who can afford to develop cutting edge algos don't program them to trade on simple indicators everyone knows about, such as moving averages.

It's key to remember the paramount goal of investing is to buy low, sell high. That part never changes.

What has changed, though, is we're now competing with unemotional robots that can be programed to be greedy when others are fearful and vice versa.

Remember the waterfall market environment last December? That was a chance to buy low. The optimal entry point turned out to be December 24th, when the S&P 500 was at its maximum gap below the 200-day moving average.

Experiences like last December, where sharp selloffs suddenly reverse course and whipsaw investors, are more common than bear markets. That's one more reason to be weary about using moving averages as a stop-loss mechanism.

From 1980 - 2018, U.S. stocks declined over -10% on 36 occasions (source: Investopedia). Only on five of those occasions did the corrections turn into bear markets, i.e. protracted declines exceeding 20%. Stock market corrections of 10% or more happen on average about once per year. Only 14% of the time do they result in a bear market.

I'm a fundamental investor, but I also use technical indicators. Like it or not, timing matters.

There's one key difference in the type of indicators I use, though. Rather than extrapolating present trends forward, they focus on identifying trend exhaustion zones.

Examples of indicators anyone can use to help identify trend pivots include: AAII Bull/Bear surveys, CNN's Fear/Greed Index, Citi's Economic Surprise Index, and Put/Call ratios.

If you can afford them, DeMark Indicators are the best.

The key advantage of exhaustion indicators is they proactively identify where trend pivots are probable (bullish or bearish). Hence, they provide objective cues to help achieve our paramount goal as investors: buying low and selling high.

Moving average strategies, on the other hand, emphasize what already happened in the rear view mirror. That's no way to drive your portfolio, especially in 2019.

*Originally published by Forbes. Reprinted with permission.

This material is not intended to be relied upon as a forecast, research or investment advice. The opinions expressed are as of the date indicated and may change as subsequent conditions vary. The information and opinions contained in this post are derived from proprietary and nonproprietary sources deemed by Silverlight Asset Management LLC to be reliable, are not necessarily all-inclusive and are not guaranteed as to accuracy. As such, no warranty of accuracy or reliability is given and no responsibility arising in any other way for errors and omissions (including responsibility to any person by reason of negligence) is accepted by Silverlight Asset Management LLC, its officers, employees or agents. This post may contain “forward-looking” information that is not purely historical in nature. Such information may include, among other things, projections and forecasts. There is no guarantee that any of these views will come to pass. Reliance upon information in this post is at the sole discretion of the reader.

Testimonials Content Block

More Than an Investment Manager—A Trusted Guide to Financial Growth

"I’ve had the great pleasure of having Michael as my investment manager for the past several years. In fact, he is way more than that. He is a trusted guide who coaches his clients to look first at life’s bigger picture and then align their financial decisions to support where they want to go. Michael and his firm take a unique and personal coaching approach that has really resonated for me and helped me to reflect upon my core values and aspirations throughout my investment journey.

Michael’s focus on guiding the "why" behind my financial decisions has been invaluable to me in helping to create a meaningful strategy that has supported both my short-term goals and my long-term dreams. He listens deeply, responds thoughtfully, and engages in a way that has made my investment decisions intentional and personally empowering. With Michael, it’s not just about numbers—it’s about crafting a story of financial growth that has truly supports the life I want to live."

-Karen W.

Beyond financial guidance!

"As a long-term client of Silverlight, I’ve experienced not only market-beating returns but also invaluable coaching and support. Their guidance goes beyond finances—helping me grow, make smarter decisions, and build a life I truly love. Silverlight isn’t just about wealth management; they’re invested in helping me secure my success & future legacy!"

-Chris B.

All You Need Know to Win

“You likely can’t run a four-minute mile but Michael’s new book parses all you need know to win the workaday retirement race. Readable, authoritative, and thorough, you’ll want to spend a lot more than four minutes with it.”

-Ken Fisher

Founder, Executive Chairman and Co-CIO, Fisher Investments

New York Times Bestselling Author and Global Columnist.

Packed with Investment Wisdom

“The sooner you embark on The Four-Minute Retirement Plan, the sooner you’ll start heading in the right direction. This fun, practical, and thoughtful book is packed with investment wisdom; investors of all ages should read it now.”

-Joel Greenblatt

Managing Principal, Gotham Asset Management;

New York Times bestselling author, The Little Book That Beats the Market

Great Full Cycle Investing

“In order to preserve and protect your pile of hard-earned capital, you need to be coached by pros like Michael. He has both the experience and performance in The Game to prove it. This is a great Full Cycle Investing #process book!”

-Keith McCullough

Chief Executive Officer, Hedgeye Risk Management

Author, Diary of a Hedge Fund Manager

Clear Guidance...Essential Reading

“The Four-Minute Retirement Plan masterfully distills the wisdom and experience Michael acquired through years of highly successful wealth management into a concise and actionable plan that can be implemented by everyone. With its clear guidance, hands-on approach, and empowering message, this book is essential reading for anyone who wants to take control of their finances and secure a prosperous future.”

-Vincent Deluard

Director of Global Macro Strategy, StoneX