Greed Isn't Good, But Profits Are

Submitted by Silverlight Asset Management, LLC on May 22nd, 2019

I’ve worked with hundreds of investors in my career. To date, no one has ever told me their goal was to lose money.

Yet apparently that’s becoming more of a ‘thing’ lately.

Take this recent CNBC headline:

“WeWork urges investors to see losses as ‘investments’ as it reports first-quarter loss of $264 million”

Only when you consider the broader environment—where negative earnings and interest rates are becoming the new normal and Modern Monetary Theory is circulating through the halls of Congress—does it become clear why such a pitch may find a receptive audience.

We live in a time when profits don’t seem to matter much.

IPOs

In 2019, we will probably see the biggest year for initial public offerings (IPOs) since 1999. Dollar volume will likely set a record, due to the rich valuations being assigned.

Sources: Harvard, Statista, HiddenLevers

The general attitude seems to be: No profits? No problem!

Many of the biggest IPOs this year—including Uber, Lyft, and WeWork—are money-losing firms. The last time this many unprofitable firms went public was in 2000.

“The rise in unprofitable IPOs reflects the general preference in both public and private markets for growth over profitability,” says PitchBook analyst, Paul Condra.

Mr. Condra is correct. A similar theme is playing out in the broader stock market. According to Gotham Asset Management, the average first-quarter return of Russell 1000 firms with negative cash flow was +31%—more than double the overall index return of +14%.

Lyft, which is down 23% since going public in March, argues it could have been profitable if it didn’t spend as much on R&D or advertising. But then again—they probably wouldn’t attract as many customers without such spending, right?

Negative Interest Rates

In Europe, interest rates are once again traversing the zero boundary, weighing on global rates. The last time this occurred was in early-2016. That time around, global equities staged a powerful rally. A similar experience may now be underway.

European 10-Year Bond and Global Equities

Sources: Bloomberg, Silverlight Asset Management

Falling interest rates tend to spark higher valuations, and the S&P 500’s forward P/E multiple has risen to 17.7x from 14.6x at the start of the year.

But then again—maybe everything is a bid when money is free?

Below is the exact same interest rate graph overlaid against bitcoin (green line).

European 10-Year Bond and Bitcoin

Sources: Bloomberg, Silverlight Asset Management

Does the return to negative rates have something to do with bitcoin’s dramatic rebound in 2019? That would make sense, given how bizarre and manipulated the bond market has become.

Last week, I ran a screen and identified over 11,300 government and corporate bonds where the holders are guaranteed losses if they hold to maturity. The amount of government debt with negative yields rose over $10 trillion in the spring.

More troubling to me, though, is the $200 billion worth of negative-yielding corporate bonds. Every corporation has credit risk. Yet that doesn’t seem to be priced-in right now.

For instance, in recent months French firms LVMH and Sanofi both issued bonds at sub-zero rates. Investors gobbled them up. According to the Financial Times, the LVMH placement saw six times as many orders as the bond’s €300 million size.

Why would professional investors buy bonds they know will lose money if held to maturity?

A few reasons:

- Many institutional managers and passive funds are required to buy bonds based on asset allocation mandates.

- There is a legit cost to hold cash. Big financial institutions can’t stuff hundreds of millions of dollars under mattresses.

- Negative yielding bonds are very price sensitive. Some of the bond buying may be attributable to speculation and the ‘Greater Fool Theory’.

Most bond mandates stem from the idea bonds are “safe.” But is that true at any valuation? The 30-year treasury yield of 2.8% is equivalent to a P/E ratio of 36x. At negative rates, you can’t even calculate a P/E.

Modern Monetary Theory

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is a fancy name for printing money to support fiscal endeavors. It’s easy to understand the allure.

Healthcare for all? MMT can pay for it.

Universal income? MMT can pay for that, too.

With MMT, the government could theoretically deposit money into peoples' bank accounts indefinitely.

And if inflation gets out of hand, no worries. MMT proponents argue you just raise taxes.

Is the key to good jobs and shared prosperity as simple as printing more money?

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez appears to think it’s an idea worth considering. On the other side of the aisle, Marco Rubio seems open to it as well.

It’s like economic and political nirvana all wrapped into one. Unlimited money, unlimited handouts, no consequences for bad behavior.

Yet there’s also a nagging issue that hovers in the background… What is money worth if money is free and unlimited?

The quantitative easing era may explain why we seem to have entered the “The Investment Twilight Zone.” Support for such an argument grows stronger the longer things like negative interest rates persist.

***

“Money makes money, Michael.”

I remember my grandmother saying those words like it was yesterday. It was a simple lesson she drilled into my head growing up.

If you want to deconstruct how wealth is created, “Money makes money” could be the foundation of it all.

The magical elixir that creates unlimited wealth is called profit compounding.

At the simplest level, this means if someone invests a dollar today and makes a 10% return, they will have $1.10 to reinvest. Then they can earn even higher profits. That’s how money makes money in a capitalist system.

The same principle applies to corporations. Firms raise capital via debt and equity. Then it’s up to management to deploy that money productively.

What ultimately creates business value is a profit metric called Return on Invested Capital (ROIC). You hit the jackpot if you find a business that generates high profits that can be reinvested at high incremental returns.

My Grandmother bought my first stock in 1995. A coffee company called Starbucks. Turns out she made a great pick, because she correctly identified a profit compounding anomaly.

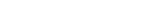

Below is a graph showing Starbucks' historical ROIC and stock price. ROIC has trended higher (white line) as new stores opened around the world. Currently, ROIC is at an all-time high and so is Starbucks' stock price (green line).

Another great thing about profits is sustainable job creation. In 1993, Starbucks had 4,585 employees. Today, the company employs over 291,000.

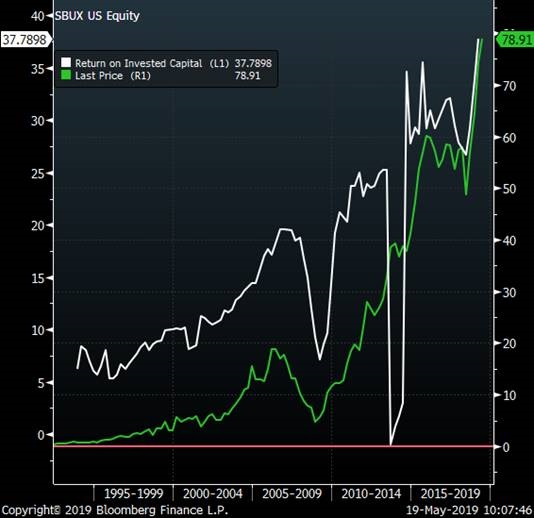

At a broader level, profitability also drives the overall stock market. The S&P 500 produced a 10% annual return from 1927–2017. As shown below, earnings-per-share growth and dividend reinvestment accounted for the vast majority of that return.

Source: Epoch Investment Partners

Bottom-line: If prosperity is a priority, profitability must stay a priority.

You can’t print or tax your way to prosperity. It must be earned. By countries, companies, and individuals.

Competition drives progress, and competitions require scorecards. Profitability provides that invaluable scorecard. And when money makes money, society becomes wealthier.

* Originally published by RealClearMarkets. Reprinted with permission.

This material is not intended to be relied upon as a forecast, research or investment advice. The opinions expressed are as of the date indicated and may change as subsequent conditions vary. The information and opinions contained in this post are derived from proprietary and nonproprietary sources deemed by Silverlight Asset Management LLC to be reliable, are not necessarily all-inclusive and are not guaranteed as to accuracy. As such, no warranty of accuracy or reliability is given and no responsibility arising in any other way for errors and omissions (including responsibility to any person by reason of negligence) is accepted by Silverlight Asset Management LLC, its officers, employees or agents. This post may contain “forward-looking” information that is not purely historical in nature. Such information may include, among other things, projections and forecasts. There is no guarantee that any of these views will come to pass. Reliance upon information in this post is at the sole discretion of the reader.

Testimonials Content Block

More Than an Investment Manager—A Trusted Guide to Financial Growth

"I’ve had the great pleasure of having Michael as my investment manager for the past several years. In fact, he is way more than that. He is a trusted guide who coaches his clients to look first at life’s bigger picture and then align their financial decisions to support where they want to go. Michael and his firm take a unique and personal coaching approach that has really resonated for me and helped me to reflect upon my core values and aspirations throughout my investment journey.

Michael’s focus on guiding the "why" behind my financial decisions has been invaluable to me in helping to create a meaningful strategy that has supported both my short-term goals and my long-term dreams. He listens deeply, responds thoughtfully, and engages in a way that has made my investment decisions intentional and personally empowering. With Michael, it’s not just about numbers—it’s about crafting a story of financial growth that has truly supports the life I want to live."

-Karen W.

Beyond financial guidance!

"As a long-term client of Silverlight, I’ve experienced not only market-beating returns but also invaluable coaching and support. Their guidance goes beyond finances—helping me grow, make smarter decisions, and build a life I truly love. Silverlight isn’t just about wealth management; they’re invested in helping me secure my success & future legacy!"

-Chris B.

All You Need Know to Win

“You likely can’t run a four-minute mile but Michael’s new book parses all you need know to win the workaday retirement race. Readable, authoritative, and thorough, you’ll want to spend a lot more than four minutes with it.”

-Ken Fisher

Founder, Executive Chairman and Co-CIO, Fisher Investments

New York Times Bestselling Author and Global Columnist.

Packed with Investment Wisdom

“The sooner you embark on The Four-Minute Retirement Plan, the sooner you’ll start heading in the right direction. This fun, practical, and thoughtful book is packed with investment wisdom; investors of all ages should read it now.”

-Joel Greenblatt

Managing Principal, Gotham Asset Management;

New York Times bestselling author, The Little Book That Beats the Market

Great Full Cycle Investing

“In order to preserve and protect your pile of hard-earned capital, you need to be coached by pros like Michael. He has both the experience and performance in The Game to prove it. This is a great Full Cycle Investing #process book!”

-Keith McCullough

Chief Executive Officer, Hedgeye Risk Management

Author, Diary of a Hedge Fund Manager

Clear Guidance...Essential Reading

“The Four-Minute Retirement Plan masterfully distills the wisdom and experience Michael acquired through years of highly successful wealth management into a concise and actionable plan that can be implemented by everyone. With its clear guidance, hands-on approach, and empowering message, this book is essential reading for anyone who wants to take control of their finances and secure a prosperous future.”

-Vincent Deluard

Director of Global Macro Strategy, StoneX