5 Silly Things About Passive Investing Nobody Talks About

Submitted by Silverlight Asset Management, LLC on September 26th, 2019

The active versus passive investing debate is relentless. If you do a simple cost/benefit analysis, advocates of passive investing have compelling facts on their side.

- Per the latest SPIVA scorecard, 82% of U.S. large-cap equity mutual funds lagged the S&P 500 index over the last five years.

- Expense ratios for active mutual funds typically range between 0.5% to 0.75%, while most passive index funds are between zero and 0.25%.

Why pay three or four times more for a product with an 82% likelihood of an inferior outcome? It makes active management seem like a silly value proposition.

However, like so many investing topics, there are nuances worth considering.

In the interest of leveling the playing field, here are five silly things about passive investing that don’t get enough airtime.

#1: It’s silly to invest more only because something did well in the past

The energy sector represents 5% of the S&P 500 and sports a 3.8% dividend yield. Ten years ago, the sector was 15% of the index and yielded 2.2%.

Are energy stocks a better buy now compared to back then?

Dividend-focused investors may think so. But passive investors owned a lot more energy a decade ago.

According to Ben Graham, the secret to investing is to figure out the value of something and pay a lot less. He called it a “margin of safety.”

Most passive products disregard notions of fundamental value and margins of safety. They are price-driven.

The formal definition of “passive” is a market-cap weighted basket of all stocks in a market. When stocks outperform, they receive higher proportional weights, while those that lag receive lower weights. Whether or not price moves are rational is irrelevant–price is truth.

If you believe in the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH), that sort of architecture may work for you.

After you experience a few asset bubbles, however, you may come to realize the EMH is malarkey. Then it becomes a lot easier to spot dislocations and harder to ignore fundamentals.

#2: It’s silly there are more stock indices than stocks

There are over 70 times as many stock market indices as there are quoted stocks in the world (source: Index Industry Association).

Let that sink in for a moment. It’s like saying there are more teams than players in a sports league.

Why so many indices?

Tim Edwards of the index investment strategy team at S&P Global says: “The users of index-based products are more active than they’re presented to be.”

Jack Bogle, founder of The Vanguard Group, may have had altruistic intentions when he set out to create a vehicle for buy and hold investors to save money on expense ratios. But that’s not the norm.

The reason there are a ton of indexes is because they make active trading easier.

ETFs are in especially high demand when volatility accelerates. For instance, ETFs represented 37% of all U.S. equity trading in December, according to BlackRock.

#3: It’s silly how many passive products overlap

Markets are ruled by supply and demand. Passive investors should know the proliferation of ETFs created an extra layer of demand that benefits certain shares more than others.

For example, Microsoft gets direct bids from investors who study the company and choose to buy shares. Then there’s a less discriminatory demand layer from investors seeking exposure to various factor cliques Microsoft belongs to.

Examples:

- Microsoft is the #1 holding in the SPDR S&P 500 ETF ($273 billion AUM)

- Microsoft is the #1 holding in the iShares S&P 500 Growth ETF ($23.6 billion AUM)

- Microsoft is the #2 holding in the iShares Momentum Factor ETF ($10.6 billion AUM)

Last June, I profiled for Forbes readers what I called my “Ronald Miller Index.” These were stocks I thought were receiving an artificial popularity boost from momentum-based ETFs. Since that article, those stocks have lost -4.0% on average compared to a gain of +13.6% for the S&P 500.

Passive investors should tread carefully and avoid pockets where herding can create an egregious disconnect between prices and fundamentals. This is more common in growth and momentum factor ETFs than in broader market proxies.

#4: It’s silly to think anyone is purely a passive investor

Do you know anyone who consistently allocates 100% of their financial assets to one passive index fund?

I don’t.

Also, what constitutes an appropriate passive benchmark?

Many associate passive equity investing to being 100% long an S&P 500 Index Fund, like SPY.

But if someone put all their money in SPY, we could argue they’re making an active bet, since the U.S. represents only about 54% of the global market.

In reality, most “passive” investors are actively passive. Meaning: they actively rotate exposures across asset classes, countries, sectors, and styles.

#5: It’s silly to passively manage risk

When somebody buys an index fund, they are guaranteed:

100% of the index’s upside

100% of the downside

Passive investing has existed for a long time, but it has really caught on in recent years. Conditions were ripe. 100/100 is a fine ratio in an environment typified by a lot of upside and little downside.

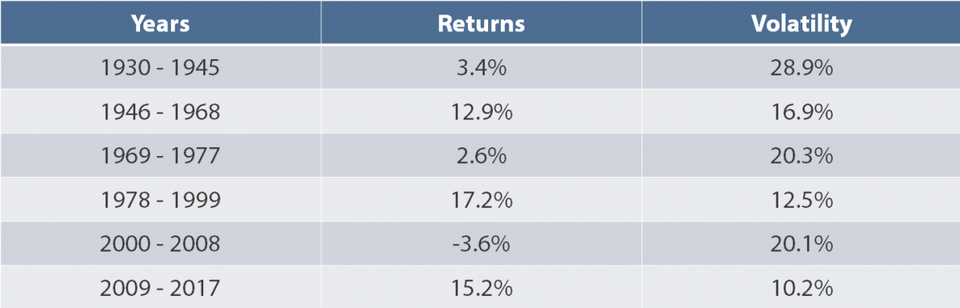

Here’s the rub, though: investment cycles mean revert. And eventually, we’re going to see a flip back to a multi-year period of lower returns and higher volatility. Will passive’s 100/100 ratio still feel like the right strategy then?

S&P 500 Cycles

It’s been well-documented in studies that investors abhor losses twice as much as they enjoy gains. That means our experience in a passive investment will not feel like 100 by 100. We feel the losses more.

Will a tiny expense ratio on a Vanguard fund seem like a bargain if the market declines over 20%?

At my firm, we don’t believe most who hire a professional money manager want someone to “passively” watch their back. So we’re in the active investing camp.

Researching stocks is a lot harder than allocating to indexes. The only reason I choose to do it is because I know active risk management can help smooth out the bumps in an investor’s journey. And at key cycle turns—it can make or break someone’s retirement.

To help illustrate how strategies can behave differently, my firm’s Core Equity Strategy has a historical upside/downside capture ratio of 94/74. This means during months when the market finished higher, we captured 94% of the upside. In months when the market generated a negative return, we were exposed to 74% of the downside. Not perfect, but we achieved positive asymmetry.

As someone who contends with market swings and the emotional swings of clients, I’m much more comfortable with my risk/reward ratio than I would be at 100/100. Especially now that we’re in a late-cycle environment.

But that’s just me. And what works for me isn’t necessarily right for everybody.

There are clearly positives and negatives to consider with passive and active investing. Depending on the framing, both approaches can appear downright silly. Conversely, both approaches can also work out well over time, if an investor has the discipline to stick with them.

Originally published by Forbes. Reprinted with permission.

Past performance is not always indicative of future results. Historical strategy results were cited for illustration purposes only. This material is not intended to be relied upon as a forecast, research or investment advice. The opinions expressed are as of the date indicated and may change as subsequent conditions vary. The information and opinions contained in this post are derived from proprietary and nonproprietary sources deemed by Silverlight Asset Management LLC to be reliable, are not necessarily all-inclusive and are not guaranteed as to accuracy. As such, no warranty of accuracy or reliability is given and no responsibility arising in any other way for errors and omissions (including responsibility to any person by reason of negligence) is accepted by Silverlight Asset Management LLC, its officers, employees or agents. This post may contain “forward-looking” information that is not purely historical in nature. Such information may include, among other things, projections and forecasts. There is no guarantee that any of these views will come to pass. Reliance upon information in this post is at the sole discretion of the reader.

Testimonials Content Block

More Than an Investment Manager—A Trusted Guide to Financial Growth

"I’ve had the great pleasure of having Michael as my investment manager for the past several years. In fact, he is way more than that. He is a trusted guide who coaches his clients to look first at life’s bigger picture and then align their financial decisions to support where they want to go. Michael and his firm take a unique and personal coaching approach that has really resonated for me and helped me to reflect upon my core values and aspirations throughout my investment journey.

Michael’s focus on guiding the "why" behind my financial decisions has been invaluable to me in helping to create a meaningful strategy that has supported both my short-term goals and my long-term dreams. He listens deeply, responds thoughtfully, and engages in a way that has made my investment decisions intentional and personally empowering. With Michael, it’s not just about numbers—it’s about crafting a story of financial growth that has truly supports the life I want to live."

-Karen W.

Beyond financial guidance!

"As a long-term client of Silverlight, I’ve experienced not only market-beating returns but also invaluable coaching and support. Their guidance goes beyond finances—helping me grow, make smarter decisions, and build a life I truly love. Silverlight isn’t just about wealth management; they’re invested in helping me secure my success & future legacy!"

-Chris B.

All You Need Know to Win

“You likely can’t run a four-minute mile but Michael’s new book parses all you need know to win the workaday retirement race. Readable, authoritative, and thorough, you’ll want to spend a lot more than four minutes with it.”

-Ken Fisher

Founder, Executive Chairman and Co-CIO, Fisher Investments

New York Times Bestselling Author and Global Columnist.

Packed with Investment Wisdom

“The sooner you embark on The Four-Minute Retirement Plan, the sooner you’ll start heading in the right direction. This fun, practical, and thoughtful book is packed with investment wisdom; investors of all ages should read it now.”

-Joel Greenblatt

Managing Principal, Gotham Asset Management;

New York Times bestselling author, The Little Book That Beats the Market

Great Full Cycle Investing

“In order to preserve and protect your pile of hard-earned capital, you need to be coached by pros like Michael. He has both the experience and performance in The Game to prove it. This is a great Full Cycle Investing #process book!”

-Keith McCullough

Chief Executive Officer, Hedgeye Risk Management

Author, Diary of a Hedge Fund Manager

Clear Guidance...Essential Reading

“The Four-Minute Retirement Plan masterfully distills the wisdom and experience Michael acquired through years of highly successful wealth management into a concise and actionable plan that can be implemented by everyone. With its clear guidance, hands-on approach, and empowering message, this book is essential reading for anyone who wants to take control of their finances and secure a prosperous future.”

-Vincent Deluard

Director of Global Macro Strategy, StoneX